There is good news in this report about emergency department care in Ontario. The data show emergency department visits are getting shorter, and that a greater percentage of visits are being completed within the provincial length-of-stay targets set for them.

Over the past seven years, the proportion of visits completed within the four-hour target for low-acuity patients who are not admitted to hospital increased to 89.9% from 84.6%, and the proportion of visits completed within the eight-hour target for high-acuity patients and admitted patients taken together as a group rose to 85.7% from 79.8 percent.

Another positive finding is that the majority of people in Ontario appear satisfied with the emergency care they receive. In 2014/15, 72.6% of respondents to a patient experience survey reported receiving excellent, very good or good care.

However, a closer look at the data reveals some troubling trends.

Emergency departments are under a great deal of pressure as Ontarians visit them more frequently than ever. Many patients wait too long in crowded emergency departments to be seen by a doctor.

So, while progress has been made in overall performance, an emergency department could be strained beyond its capacity to provide quality care to all its patients by a bad flu season, or if a hospital nearby has to temporarily close its emergency department.

Here’s what the data show:

Growth in emergency department visits is outpacing population growth. Over the past seven years, the number of annual visits to Ontario’s emergency departments increased 13.4% – more than double the 6.2% increase in the province’s population.

Visits by older patients – who tend to require more complex care – are increasing overall as Ontario’s population ages, and increasing as a percentage of all visits. Visits by people aged 65 and older rose 29.1% over the past seven years.

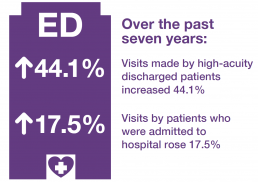

Emergency department patients are becoming collectively sicker. Over the past seven years, visits made by high-acuity discharged patients increased 44.1%, and visits by patients who were admitted to hospital rose 17.5%.

The strain that exists on emergency departments, and on other parts of the health system that affect the ability of emergency departments to provide quality care, is evident in the data.

For example, in 2014/15, the maximum amount of time within which nine out of 10 admitted patients completed their visit was 29.4 hours. A large portion of that time – 22.5 hours – was spent waiting to be admitted to hospital. These are the patients who have to endure long hours and sometimes even days lying on stretchers in examination rooms or hallways, waiting for a bed to open up in an inpatient ward.

Waits for admission are one aspect of emergency department performance linked to problems elsewhere in the health system – in this case a lack of available inpatient beds, a problem which in turn is often linked to a lack of available beds in long-term care homes.

Whatever the cause, waits in emergency for an inpatient bed are major contributors to the emergency department overcrowding that can affect the care of all patients. The consequences can include poor quality of care, increased morbidity and mortality, and increased risk of errors by overworked and overstressed medical staff.

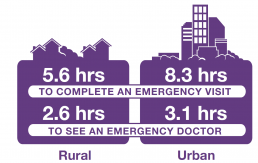

The strain on emergency department capacity is also evident in the overall longer waits for care experienced by patients who live in urban areas, where emergency departments tend to be busier and more crowded.

In 2014/15, urban residents spent longer in the emergency department and had longer times to physician initial assessment than those living in rural areas. Approximately 86% of people in Ontario live in urban areas.

The maximum amount of time within which nine out of 10 urban residents completed their emergency visit was 8.3 hours overall for all acuity levels, compared to 5.6 hours for rural residents, while the maximum amount of time nine out of 10 urban residents waited to see a doctor in emergency was 3.1 hours overall for all acuity levels, and 2.6 hours for rural residents.

The data also indicate that some people may be going to emergency for health problems that don’t require emergency department care – another factor contributing to overcrowding that is related to issues elsewhere in the health system. In a 2013 survey, 47% of adults in Ontario reported going to emergency for a condition they thought could have been treated by their primary care provider, if that doctor, nurse practitioner or other provider had been available.

Many individuals and organizations have tried hard to improve the quality of care provided in Ontario’s emergency departments. The Emergency Room Wait Times Strategy launched in 2008 and then expanded by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care has brought positive results in areas such as patient satisfaction and length of stay.

As Ontario’s population grows and ages and emergency visits are likely to continue to increase, the pressure on emergency departments to handle more and sicker patients with greater efficiency will likely continue and even intensify.