Emergency departments are doing better

The good news is that the performance of Ontario emergency departments in all three of these indicators has improved overall in recent years, despite increases in the volume, age and acuity of patients.

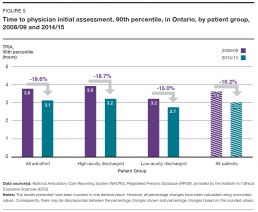

Between 2008/09 and 2014/15, the 90th percentile time to physician initial assessment – the maximum amount of time within which nine out of 10 patients saw a doctor – decreased by:

- 16.2% overall for all patients, to 3.0 hours from 3.6

- 18.7% for high-acuity discharged patients, to 3.2 hours from 3.9

- 15.0% for low-acuity discharged, to 2.7 hours from 3.2

- 19.6% for admitted patients, to 3.1 hours from 3.8 [2] (Figure 5)

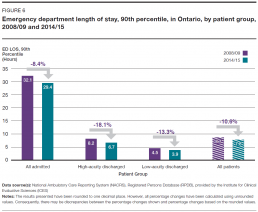

Over the same period, the 90th percentile length of stay in the emergency department – the maximum amount of time within which nine out of 10 patients completed their visit – decreased by:

- 10.6% overall for all patients, to 7.8 hours from 8.7

- 18.1% for high-acuity discharged patients, to 6.7 hours from 8.2

- 13.3% for low-acuity discharged patients, to 3.9 hours from 4.5

- 8.4% for admitted patients, to 29.4 hours from 32.1 [2] (Figure 6)

Also over those seven years, the proportion of emergency visits completed within the province’s four-hour length-of-stay target for low-acuity discharged patients increased to 89.9% from 84.6%. The proportion of visits completed within the eight-hour target for high-acuity patients and admitted patients, when lengths of stay for those two categories of patients are counted together in a single group, rose to 85.7% from 79.8%.[11]

The annual number of emergency department visits that resulted in the patient leaving without being seen by a doctor decreased by 18.3% between 2008/09 and 2014/15, to approximately 3% of all visits from about 4%. Some research suggests the most common reason for leaving the emergency department is being “fed up with waiting.”[12]

Another important quality indicator is patient experience. The majority of people in Ontario appear to be satisfied with the care they have received in the province’s emergency departments. In a 2014/15 patient experience survey of Ontarians aged 16 and over conducted on behalf of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 72.6% of respondents reported receiving excellent, very good or good care. However, the other 27.4% – more than one in four respondents – rated their care as fair or poor.[13]

There were fewer positive ratings among people aged 16 to 44, at 68.8%, and more from people aged 75 and older, at 86.7%. Among rural residents, 83.5% rated their experience as positive, compared to 70.6% of urban residents.[13]

Improvement still needed in some areas

Even though lengths of stay and waits to see a doctor were shorter, and the majority of patients were satisfied, emergency departments were not necessarily performing as well as they should be for all patients.

Admitted patients may spend a long time in emergency

Why the 90th percentile?

Time to physician initial assessment and emergency department length of stay are measured in this report at the 90th percentile – the amount of time within which nine out of 10 patients will have seen a doctor or completed their visit.

The 90th percentile indicator was chosen because it represents the maximum wait to see a doctor or length of stay for the vast majority – 90% – of patients. So, it’s a point of measurement that includes most extreme scenarios in which patients have to wait longer to see a doctor or stay longer in emergency than patients at the median or average time points.

Provincial and individual hospital targets for length of stay and time to physician initial assessment are also set at the 90th percentile, to more fully reflect what the emergency department experience may be like for a wide range of patients.

While the 8.4% decrease in the 90th percentile length of stay for admitted patients was a significant improvement, that still meant nine out of 10 admitted patients spent up to 29.4 hours in the emergency department in 2014/15. A large portion of that time – 22.5 hours – was spent waiting in the emergency department to go to an inpatient ward.[2]

There are several consequences that may arise from emergency patients having to wait such a long time for admission to an inpatient hospital bed. They include discomfort for the patient and possibly less than optimum care as a result of not being in the hospital ward a doctor has decided is best suited for their care.

As well, because they usually have to occupy a bed in emergency while they wait, sometimes for many hours, admitted patients may impede access to emergency beds, doctors, nurses and other resources for other patients still waiting for care.

A lack of available inpatient beds for patients from emergency may be linked to many possible factors. For example, a hospital may simply not have enough beds to meet the needs of the growing community it is serving;[14] inefficient inpatient bed management may lead to patients not moving in and out of hospital wards as quickly as possible; or, inefficient housekeeping practices may mean inpatient beds are not readied for the next patient quickly enough.[15]

Lack of inpatient bed availability is also frequently attributed to inpatient beds being occupied by patients who don’t require hospital care but are waiting for a space in a health care facility appropriate for their needs – such as a long-term care home or a rehabilitation facility. These patients are often identified as requiring an “alternate level of care.”

In 2014/15 in Ontario, 13.7% of “inpatient days,” or of all the days each individual hospital bed in the province was occupied by a patient, were used for patients identified as needing an alternate level of care.[16] That was an improvement, down by 14.3%* in 2011/12. The 2014/15 figure amounted to approximately 4,000 inpatient days being used at any given time that year for patients waiting to receive care elsewhere.

To whatever extent patients requiring an alternate level of care may affect emergency department lengths of stay, it is an issue for which at least part of the solution lies in other parts of the health system. Hospitals can certainly work on improving the flow of patients through their emergency departments and inpatient wards, but there is not much they can do to free up inpatient beds occupied by patients waiting for places in long-term care homes, for example.

*Incomplete fiscal year: July 2011 – March 2012.