Visits are on the rise

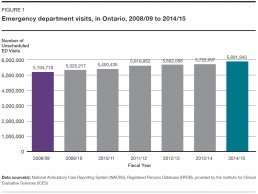

In 2014/15, people in Ontario made approximately 5.9 million visits as patients to emergency departments (Figure 1). That was a 13.4% increase over the 5.2 million visits they made in 2008/09.[2] Over the same period, the province’s population increased by 6.2%.[3]

The number of annual visits to the emergency department is likely to keep rising since Ontario’s population is projected to increase by 30% over the next quarter century.[3]

Patients are getting older

At the same time as Ontario’s emergency departments have been dealing with an increasing volume of patients, those patients’ needs have been changing.

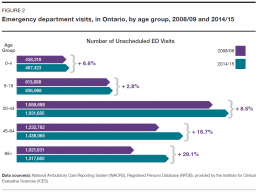

In 2014/15, people aged 65 and older made approximately 1.3 million visits to emergency departments, an increase of 29.1% over the 1 million visits they made in 2008/09 (Figure 2). Visits by all the patients in other age groups combined rose by 9.6% over the same period. While the percentage increase in visits by the 65-plus group was the biggest, it increased for all age groups.[2]

The proportion of visits made by people 65 and older increased to 22.4% of all visits in 2014/15, from 19.7% in 2008/09. In 2014/15, this equated to about 60 visits per 100 people aged 65 and older in Ontario.

This pattern of increased visits by older adults is likely to accelerate in coming years, since the number of people aged 65 and older in Ontario is projected to more than double over the next quarter century, and the proportion of the population in that age group will increase to 25.3% from 16.0%.[3]

The overall aging of the population will likely increase the need for the more complex emergency care older adults tend to require.

Older adults frequently need more complex care because they often experience symptoms that make the cause of their health problem difficult to diagnose; they may suffer from side effects associated with the multiple medications many take; they may have several chronic diseases that require concurrent treatment; they may have physical disabilities that require assessment and management; and some might have cognitive problems that make it difficult for them to describe their health issues, understand what they are being told, or follow up on their care once they leave emergency.[4]

Overall, older patients are more likely to spend a longer time in emergency and are more likely to be admitted, compared to their younger counterparts.[5]

The overall aging of the population will likely increase the need for the more complex emergency care older adults tend to require.

— Under Pressure: Emergency Department Performance in Ontario

People are coming to emergency sicker

The patient’s time in emergency

There are a number of factors that affect the length of a patient’s stay in the emergency department.

First, the nature of their health problem and the acuity level assessed for it at triage will help determine how long it will take before the patient sees a doctor. If the doctor orders diagnostic tests such as x-rays or blood work, those will have to be completed and processed before the patient sees the doctor again to discuss the results.

The visit may also include a consultation with a specialist, more tests, treatment, an observation period to see the results of treatment, or a wait for a decision by a doctor on whether the patient should be admitted to the hospital, sent home or transferred to another facility.

If they are admitted, there will likely be a wait for an inpatient bed; if they are discharged home, there may be a wait for instructions on self-care or for follow-up with a doctor in the community; and if they are transferred, there could be a wait for an ambulance to transport them to another care facility.

While the patient’s own needs are key to determining their path through emergency, if other people in emergency have more urgent need for diagnosis and treatment, that may result in longer waits for care that prolong the patient’s visit, and could affect the amount of time and attention the patient receives from individual members of staff.[9]

Partially as a result of the growth in visits by people aged 65 and older, there has been an increase in emergency department visits by patients with serious health conditions, as indicated by the number who are admitted to hospital, and by their scores on the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS).

The CTAS scale prioritizes patients by urgency to help determine the order in which they are seen and treated. Every emergency patient is assigned a CTAS score when they undergo triage – a brief assessment of their condition – shortly after arrival.

For the purposes of the indicators used in this report, patients are divided into three groups. To do that, patients were first identified according to their CTAS scores as either “high-acuity” or “low-acuity.”

High-acuity patients have conditions that, as described by the CTAS guidelines, may threaten their lives and require immediate aggressive intervention; or that are a potential threat to life or limb function and require rapid medical intervention; or that could potentially progress to a serious problem requiring aggressive or rapid intervention.[6]

Low-acuity patients have conditions that would benefit from medical intervention or reassurance within two hours; or for which investigation and treatment could be delayed or referred to other areas of the hospital or health system.[6]

Patients at either acuity level may be discharged home after their visit, admitted as an inpatient to the hospital, or discharged to be transferred to another health facility.

High-acuity patients who are not admitted are referred in this report to as “high-acuity discharged,” and low-acuity patients who are not admitted are referred to as “low-acuity discharged.” All patients at either acuity level who are admitted to the hospital are grouped together and referred to as “admitted” patients.

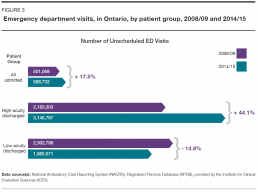

Between 2008/09 and 2014/15, the number of emergency department visits made annually by high-acuity discharged patients increased 44.1%, to approximately 3.1 million visits from 2.2 million, while the number made by low-acuity discharged patients decreased 14.6%, to approximately 2.0 million visits from 2.3 million. Visits by admitted patients rose 17.5%, to approximately 589,000 visits from 501,000. (Figure 3).

These changes over time shifted the overall acuity level of the patient caseload handled by Ontario’s emergency departments. Visits by high-acuity discharged patients rose to 53.4% of all visits by all patients, from 42.0%. Visits by low-acuity discharged patients fell to 33.4% of all visits, from 44.3%. Only visits by patients who were admitted remained relatively steady, increasing to 10.0% of all visits from 9.6%.[2]

Increases in high-acuity discharged and admitted patients were more pronounced among patients in the 65-plus age group. Between 2008/09 and 2014/15, the number of annual visits by patients aged 65 and older who were categorized as high-acuity discharged increased by 59.7%, compared to a rise of 40.2% for all other patients in that category. Visits by patients in the older age group who were admitted to hospital increased by 23.8%, compared to an increase of 11.2% for all other admitted patients.

At the same time, visits by patients aged 65 and older who were categorized as low-acuity discharged decreased 6.6%, compared to falling 15.9% for all other patients in that category.

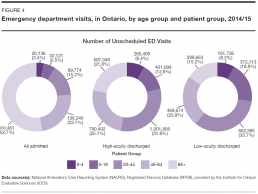

The proportion of older patients was highest among admitted patients. In 2014/15, 52.7% of admitted patients were in the 65-plus age group, compared to 21.8% of high-acuity discharged and 15.2% of low-acuity discharged patients (Figure 4).

What does it mean for patients?

Emergency departments are designed to handle a flow of many patients of different ages with many different health problems. But there are times when their capacity is strained.

When they have to deal with too many patients at once it can lead to crowding and longer stays in emergency. If more patients are sicker or older and need more complex care requiring more emergency staff and resources, that can also result in longer stays for everyone.

Long stays in emergency and long waits to see a doctor are not merely inconvenient or uncomfortable. There can be serious negative consequences when patients have to wait for care in crowded emergency departments.

Some of those consequences were outlined in a report [7] on improving access to emergency care authored by a committee of representatives from the Ontario Hospital Association, the Ontario Medical Association and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. They included: patient suffering, poor patient outcomes, increased morbidity and mortality, poor quality of care, contribution to infectious disease outbreaks and increased risk of medical error.

A number of studies have found increased risk of adverse events for patients cared for in emergency departments at times when lengths of stay were longer or they were overcrowded – with those adverse events including significant treatment delays for time-sensitive conditions, and admission to hospital or death within a week after the visit.[8,9,10]

One study analyzed deaths among non-admitted patients within a week after visiting high-volume Ontario emergency departments. The authors estimated that between 2003 and 2007, there could have been 6.5%, or 558, fewer deaths among high-acuity patients and 12.7%, or 261, fewer deaths among low-acuity patients if the average length of stay in those emergency departments had been shortened by one hour.[9]

Reasons for the increased risk associated with longer lengths of stay might include delays in treatment, or changes in the way decisions are made and care is provided when emergency staff are pressed for time amid a backlog of patients.[9,10]

Who sees the doctor first?

Triage is the process that determines the order in which emergency department patients see a doctor and are cared for. At high-volume hospitals, a “pre-triage” assessment that takes about two minutes may precede triage to determine in what order several waiting patients should be triaged.

The triage itself usually begins with a nurse asking the patient to describe their health problem and symptoms. The nurse will assess the patient’s physical appearance and their apparent degree of distress, and take vital signs such as heart rate and blood pressure as appropriate, before assigning the patient a priority score.

Hospitals in Canada must base that score on the five-level Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). The highest score is Level 1, which, according to the CTAS guidelines, would include patients with conditions such as cardiac arrest or major trauma that threaten life or pose an imminent risk of deterioration. The lowest is Level 5, which would cover patients with conditions such as a sore throat or sprained ankle for which care could be delayed or possibly referred to other areas of the hospital or health care system.

The “high-acuity” patients described in this report include patients scored at Levels 1 to 3 on the CTAS scale, while the “low-acuity” patients are those with scores of 4 or 5.

Triage depends to some extent on the instincts and experience of the health professional performing it.

“Effective triage requires the use of sight, hearing, smell and touch,” state the CTAS triage guidelines. “There are many non-verbal clues: facial grimaces, cyanosis, fear… Listen to what the patient is saying and pay attention to questions they are reluctant or unable to answer. Listen for a cough, hoarseness, laboured respiration… Touch the patient; assess heart rate and skin temperature and moisture. Notice odours such as the smell of ketones, alcohol, or infection.”[6]

The guidelines detail many factors that need to be considered in assigning a CTAS score to patients, but also encourage triage personnel to follow their instincts and experience to “up triage” patients who seem to them to require care more urgently than their symptom profile would suggest. At the same time, the guidelines say such instincts should not be used to “down triage” a patient when their symptoms suggest there may be a problem, but they look well.