Rapid Referral Clinic a win for everyone

A new way of doing things is helping to improve care for some patients coming in with complex health conditions to the busy emergency department at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Adult patients with serious health issues who need prompt, but not immediate, care may be referred by an emergency department doctor to Sunnybrook’s Rapid Referral Clinic. There, they will be seen within a few days by an internist – a doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and nonsurgical treatment of adults.

These are patients who might otherwise have to wait many hours in emergency for a consultation with an internist and for diagnostic testing, or be admitted to hospital for their condition to be investigated, or be discharged home to wait weeks or even months to see a specialist and have diagnostic tests done.

Instead, patients get to leave the emergency department with an appointment to be seen, often the next day, at the Rapid Referral Clinic.

“We have expedited access to the same type of testing that can happen in the emergency room, in order to get investigations done,” explains Dr. Graham Slaughter (photo above), who heads the clinic. Patients who need laboratory tests, or tests such as CT scans, ultrasound scans and pulmonary function tests, can have them done the same day. The clinic also has expedited access to consultations with specialists in areas such as neurology and rheumatology. And, if necessary, patients can be admitted to hospital.

Donald came to the clinic as a patient after going to the emergency department on the advice of his doctor, who was concerned when the 89-year-old developed jaundice, which can indicate problems with the liver. After spending seven hours in emergency he was referred to the clinic, where he saw Dr. Slaughter the next day.

“I was extremely impressed by him,” says Donald. “He arranged for me to have, first of all, a CT scan, and then on the results of that, a liver biopsy, all in fairly short order.”

Donald believes the clinic “cuts down on a lot of angst and worry” for patients like himself who are anxious to find out what’s wrong with them. He notes he might have had to wait a couple of months for a CT scan if he had not gone to emergency and been referred to the clinic. “Naturally if there’s a possibility of cancer lurking around in the background, it could possibly even save your life.”

Donald’s scan indicated a mass in his liver that could be cancer, so Dr. Slaughter also arranged an appointment for him with a specialist at the hospital’s cancer centre. Despite the worrisome outcome of his visit to the clinic, Donald is pleased that the time from that visit to his visit with a cancer specialist will only be two to three weeks. “Waiting is very stressful,” he says, “waiting and not knowing.”

The clinic isn’t appropriate for patients such as those who need oxygen or intravenous antibiotics, or whose condition is already being monitored by a specialist. But when referral to the clinic is appropriate, it’s a win for everyone involved.

For the hospital, it means being able to reduce emergency department crowding and admissions. For the patient, it means being able to go home and still receive the care they need in a timely manner.

“You also are trying to keep them in their own bed and as much as possible going about their lives as ordinarily as possible,” says Dr. Slaughter. “An admission can be a horribly intrusive thing.”

Sunnybrook’s own data show 22% of the patients seen at the clinic would have been admitted to hospital if it were not available. The clinic has also created cost efficiencies that freed up approximately $1 million per year. And, it has resulted in satisfied patients.

“Patients seem to be genuinely happy with the effort that’s put forward, with the relative speed at which they get seen and the thoroughness of the work that we do,” says Dr. Slaughter.

Certain population groups do not have the same emergency department experience as others – with some groups collectively staying longer in emergency or spending a longer time there before seeing a doctor, and some visiting emergency more often. Some of these differences in patient experience and utilization point to possible inefficiencies and inequities in the health system as a whole.

Urban residents spend more time in emergency

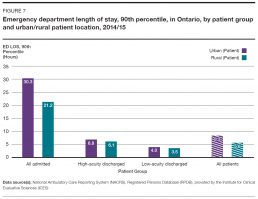

In 2014/15, patients living in urban areas spent longer in the emergency department and waited longer to see an emergency doctor than those living in rural areas. This was true regardless of acuity level. Approximately 86% of people in Ontario live in urban areas.[17]

The 90th percentile length of stay in emergency for urban residents was 8.3 hours overall for all acuity levels, compared to 5.6 hours for rural residents. The biggest difference in stay lengths was for admitted patients, with urban admitted patients spending up to 30.3 hours in emergency at the 90th percentile, while rural admitted patients spent up to 21.2 hours (Figure 7).

The 90th percentile time to physician initial assessment for urban residents was 3.1 hours overall for all acuity levels, and 2.6 hours for rural residents.

Stays in emergency and waits to see a doctor could be longer for urban residents because patient length of stay and time to physician initial assessment are longer in teaching and community hospitals, which are usually located in urban centres and are usually more busy and crowded.

For example, in 2014/15, the 90th percentile length of stay for all emergency patients at teaching hospitals in Ontario was 11.0 hours, compared to 7.6 hours for community hospitals and 4.3 hours for small hospitals.[2]

Residents of low-income neighbourhoods visit the emergency department more often

People from low-income neighbourhoods go to the emergency department more frequently than those from higher-income neighbourhoods. In 2014/15, 23.4% of the one-fifth of Ontario’s population living in the lowest-income neighbourhoods visited an emergency department, compared to 16.6% of the one-fifth of the population living in the highest-income neighbourhoods.[2]

The possibilities suggested by this finding include that people from low-income neighbourhoods may be less able to access care elsewhere, may be unable to access care in time to prevent the need for an emergency visit, or may be less healthy and need emergency health care more often.

Similar factors may be at play for residents of rural regions, who in 2014/15 visited the emergency department at a rate of 59 visits per 100 people, compared to 40 visits per 100 for urban residents.[2] Research suggests a greater proportion of primary care in rural areas is delivered through hospitals and emergency departments, particularly where few after-hours services are available.[18,19]

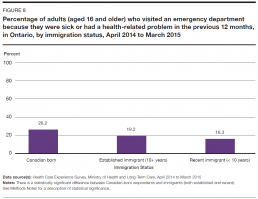

Recent immigrants make fewer visits to the emergency department

Some people are going to the emergency department less often than others. In 2014/15, among Ontarians who immigrated to Canada within the previous 10 years, 16.3% reported visiting an emergency department in the previous 12 months, compared to 19.2% of established immigrants in the province, and 26.2% of those born in Canada (Figure 8).[13]

Could some emergency patients be cared for elsewhere?

In 2014/15, 33.4% of all visits to the emergency department were made by patients who were categorized as having low-acuity conditions and were discharged home after their visit.

It’s not clear exactly what proportion of people who go to the emergency department for low-acuity conditions could be treated by a primary care provider. Patients with low-acuity conditions may need emergency department care, for example, to deal with a complex wound.

In 2013/14, an estimated one in five emergency department visits in Canada by patients who were not admitted to hospital were for conditions that can be treated at a doctor’s office or clinic, such as sore throats and ear infections.[20]

Nor is it clear how much the number of low-acuity patients flowing into emergency departments affect the quality of care received by all emergency patients.

Certainly, low-acuity patients, like all patients, contribute to whatever overcrowding exists in emergency departments. As well, their care requires the use of limited emergency department resources such as doctors, nurses, medical technicians, clerical staff, equipment, and diagnostic imaging services, which may affect the availability of those resources for the care of sicker patients.

However, low-acuity patients are usually the quickest and easiest to deal with and data show they are in and out the fastest. They probably do not slow down the flow of patients as much as, for example, high-acuity patients who need a lot of tests and consultations or who occupy space in emergency departments for hours while waiting for admission to hospital.

An Ontario study that looked at all visits to emergency departments over a one-year period found that the presence of low-acuity patients was associated with an insignificant increase for other emergency patients in length of stay and wait time to see a doctor. It concluded that reducing the number of low-acuity patients was unlikely to lessen emergency department crowding or shorten stays or waits to see a doctor for other patients.[21]

Treating a patient with a low-acuity condition in primary care may be less expensive than treating them in an emergency department. The average cost of a visit to emergency in Canada has been estimated at five times the cost of a visit to a family practitioner – though the calculation of the average cost for an emergency visit included high-acuity patients.[22]

However, the marginal cost of treating a low-acuity patient in emergency may not be higher in some cases – considering the emergency department resources required are usually already in place, while the primary care resources required to provide the same service may not be.

The extent to which Ontarians use emergency departments for low-acuity conditions appears to be related at least partially to a problem in another part of the health system – lack of timely access to primary care.

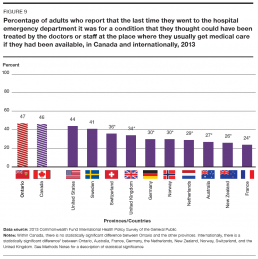

In a 2014 survey, 94% of people in the province aged 16 and over said they had a family doctor or other primary care provider, but only 44% reported being able to get an appointment with them the same or next day when they were ill.[23]

In 2013, almost half of adult Ontarians – 47% – reported going to the Emergency Department for a condition they thought could have been treated by their primary care provider, if that doctor, nurse practitioner or other provider had been available. This rate was higher for Ontario than for its socioeconomically similar international counterparts, with Switzerland coming in at 36% and France lowest at 24% (Figure 9).[24]

Rosemary: A long wait in pain

Rosemary’s back pain took a horrible turn for the worse immediately after she took what was supposed to be a soothing bath on the advice of her physiotherapist.

“I was standing in my bathroom and I suddenly had this pain, but it was overwhelming,” she recalls. “That’s all I remember, standing in the bathroom with this pain and then the next thing I remember I’m waking up and my head is beside the toilet and I’m lying on the bathroom floor and all I could do was scream.”

Rosemary crawled very slowly to her bed. She didn’t go to emergency until she could find someone to look after her three dogs. After she called 911 and was taken by ambulance to an urban community hospital emergency department, Rosemary waited five or six hours on a stretcher in a hallway before a doctor saw her. The pain medication she had been taking at home had begun to wear off soon after her arrival.

“They told me I couldn’t take anything that wasn’t administered by them and they were too busy to see me, and I’m lying there in complete agony with no help.” She says she was in a hallway for her entire 15-hour stay in emergency, except for the brief periods when she was taken for testing and catheterization.

“I think two or three doctors came to me while I was in emerg. They asked me the same questions: ‘Do you know what happened? What do you think caused it?’ Two, three minutes and then they were gone. The third guy, which I suspect was like eight hours there now, gave me a pain pill which didn’t take the pain away, just made me feel a little bit better.”

“It’s not like the people there aren’t trying. They’re just overwhelmed…”

After a CT scan was done, Rosemary was told she appeared to have a large but non-malignant tumour at the base of her spine, and that she would have an MRI scan to determine exactly what was wrong. She was given medication called gabapentin, which made the pain go away for about an hour-and-a-half at a time, and a few hours later she was admitted to the hospital as an inpatient.

But Rosemary says some misunderstanding or miscommunication must have occurred because she was in a lot of pain but was no longer given gabapentin in the inpatient ward, even though she had told the nurse in emergency that it relieved her pain. She says such problems could be dealt with more effectively if patients had immediate access to their records, because she saw in her records after leaving the hospital that the nurse had written that Rosemary didn’t want gabapentin.

The MRI scan showed Rosemary had a ruptured disc that had initially looked like a tumour because so much disc material had escaped. She spent 10 days in hospital and a year incapacitated at home, and is still not able to do all the things she did six years ago before her injury.

Rosemary says she has visited emergency departments about a dozen other times over the past eight years and the visits have lasted eight or nine hours each time. She believes that’s too long and that emergency care can and should be improved.

“It is not efficient, it is not functioning well. It’s not like the people there aren’t trying. They’re just overwhelmed, and when people get overwhelmed they actually get less productive.”